Newtopia Magazine

"Last summer, someone at work called me 'cutie' - and only now, after taking this class, do I realize how offensive that was," announced a petite blonde sitting next to me in a classroom full of women. Some nodded with approval, others lowered their eyes sympathetically, but none smiled.

This is, indeed, an excellent reason to attend college, I thought. Where else can you find a women's support group but in a class that requires a diligent, semester-long recital of the "women are victims, men are monsters" mantra, a class containing in its title the sacred trinity of "gender, class and race"? The four males taking the class were frozen down into their chairs most of the time, and when one found courage, during a discussion of the evils of film industry, to remark on the subtlety of Quentin Tarantino's work, he drew only blank stares from the audience and a dry "Who?" from the professor.

In this class, which I took the first semester of my grad school, I felt and acted as a traitor to my gender. I reached the highest point of my infidelity when I stumbled upon an idea for the midterm research paper: it had nothing to do with women, class or race; I chose to write about anti-Muslim bias in major U.S. newspapers' coverage of the Oklahoma City bombing.

In the fall of 1996, unlike now, this theme was not self-evident, and I was lucky to have eavesdropped on a conversation between two of my next-door neighbors. One, a Muslim boy I would spend the next two years desperately trying to befriend, spoke about some truly outrageous things that had happened to American Muslims in the first few days after the blast. The other - a man who would stalk me for the next year or so - knew about the injustices and kept the conversation going long enough for me to see that this was my chance to escape the dogmatic limitations of the gender discourse imposed on me that semester.

The woman in me failed to feel degraded when I followed this lead from the two silly men bent on trying my patience - each in his own spectacular way - as no one else had ever had. The woman in me was not disturbed by the fact that I was writing about people whose religion seemed to deprive certain women's rights activists of their sleep. The woman in me effortlessly erased the recent memories of Middle Eastern engineering and medical students in the streets of Kyiv, Ukraine, yelling "Habibi! Hey, ha-beee-beee!" at me, as I walked by with all the dignity I could assemble (their shouts, in this context, could be roughly translated from Arabic as "Hey, baby!").

Eventually, the woman in me triumphed as the professor gave me an 'A' for the paper and asked me to present it in class. But my dissident spirit suppressed the woman in me and talked me out of this submissive act, returning me to the traitor's orbit.

A year and a half later, I was back home in Ukraine, crushed by the revelation that regardless of my views on feminism, Islam, ethnic and other minorities, freedom of the press and just about anything else, I was doomed to a career of an English tutor. By December 1998, I had four students and an income of approximately $200 a month. I wasn't starving; moreover, I was beginning to notice those tiny little things that I couldn't exactly control but was sort of able to keep from slipping away. I made my room look like my room again by convincing my parents that they didn't need so much extra storage space; I fell in love with reading local newspapers and secretly dreamed of doing a dissertation that might later inspire me to launch a Russian/Ukrainian branch of The Onion; I got used to a typewriter and resumed writing.

Then one day I realized that my U.S. driver's license was about to expire. Its actual value at the time was nil, for there was no way I could afford a car or dare navigate it through the jumble of European-standard road signs and swarms of corrupt traffic cops. Yet, the symbolic significance of this plastic card was immense: it certified my ascension to the class of drivers, which no one in my immediate family had ever belonged to, and to a less numerous subclass of female drivers, known in the former Soviet Union mainly as "the killers on the road" (a stereotype I had been consciously, and successfully, trying to defy while I was in the United States). Letting the license expire equaled to having my master's degree in journalism annulled, an incident that wouldn't have had any impact on my everyday life but that would still have obliterated a huge part of my dear little self. This peril had to be averted at any cost, and so, without delay, I set out to obtain a Ukrainian driver's license.

The first step (or, to be precise, a series of steps) was to have a myriad of doctors confirm that I was a healthy individual. Briefly, the woman in me appeared to be quite a burden because, in addition to a checkup of my eyes, ears, nose and throat, as well as an inspection of a matchbox of my feces and a jar of my urine (a routine required of both males and females aspiring to drive a vehicle), I had to pay a visit to a gynecologist. Or so I thought at first. After some reconnaissance, I encountered a young doctor willing to sacrifice his integrity and provide me with all but two of the needed certificates for just $10. The un-bribable personnel of this hospital included a psychiatrist and a doctor known in our part of the world as "a narcologist."

For a number of reasons, I was not all too eager to meet a Ukrainian psychiatrist. I sat on a chair by his office, tense, waiting and listening to a Russian pop song that was coming from behind the closed door. Soon, a man appeared down the hallway; he smoked a cigarette as he walked, and when he approached me, I was struck by how familiar he looked: dressed in a white gown, he looked like a more mellow Karl Marx. He nodded, inviting me in, discarded his cigarette into a sink in the corner of the room, asked my name, and on a pre-stamped form wrote down his judgment. In his opinion, I was mentally fit to drive a car.

Filled with enthusiasm, I expected similar brevity from the narcologist - a quick look at my veins, perhaps, and a friendly suggestion or two about how dangerous it was to do drugs and to drink and drive. But first, a nurse took my blood sample. Then she accompanied me to a small auditorium where half a dozen more people, mostly men, were seated, listening to a bespectacled woman, the narcologist, whose white gown didn't manage to conceal her intimidating, high-school teacher appearance. I realized I was late for something when she paused for just a second to give me a harsh glance.

For the next two hours, she talked about everything I never wanted to know about car accidents and the subsequent first aid. I may still remember how to tell whether someone is experiencing clinical death or is actually dead; I know that it's worth trying to resuscitate a person for as long as 50 minutes; I have been warned that when someone's internal organs are lying next to him on the ground, I should never attempt to put them back inside the person, for this will most likely cause peritonitis. "If a person is unconscious," the narcologist said by the end of her lecture, "you need to take his tongue out of his mouth and pin it down to his shirt. Please note: to his shirt, not to his cheek - even though it's not your cheek so you don't care." All of a sudden, I found myself asking a truly journalistic question: "Excuse me, and how long is the human tongue?" She chuckled and gave me the most excruciating quote in my life: "Miss, it's the shirt that you're gonna pull towards the tongue, not vice versa!"

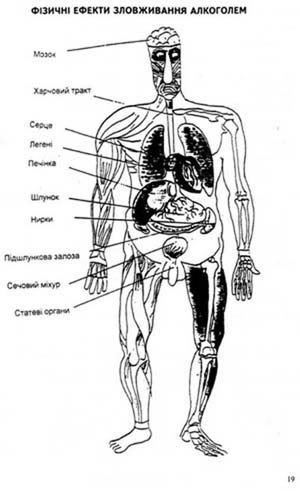

She spent the last fifteen minutes speaking about zero tolerance, the four hours that it takes 50 grams of vodka to vanish from our blood, and the spooky "physical effects of alcohol abuse" (see illustration below). When she was done, a line quickly formed by her table. Two men - truck drivers who had to go through this ordeal every two years - were the first to get the narcologist's signature. "Why such a hurry?" she inquired, as they were elbowing their way to the door. One of the men turned around, smiled a conspiratory smile and replied: "Time for a drink!"

"Physical Effects of Alcohol Abuse" (from a booklet distributed by a narcologist to practicing and wannabe Ukrainian drivers)

When my turn came, the narcologist crossed off a square on the form that said that I normally had one drink a week - wine or champagne. I had a question mark in my eyes, and she explained: "This is what all the girls who come to us say--they don't like vodka or cognac." I pointed out that beer in this country was extremely good, but she had already signed the paper, and I was free to go, for once feeling as a very good, average Ukrainian woman - not really myself, but that was the last thing I cared about at the end of that long day.

The next step was actually getting the driver's license, and it was a much more pleasant experience, if somewhat shameful again. My still-valid U.S. license helped me avoid the obligatory, state-administered driving classes. A few useful connections, and chocolate and cognac for bribes, transported me over much of the red tape that rules Ukrainian traffic police. I landed right onto a relatively small but comfortable red carpet that led me to my goal, by way of an anonymous police boss - a useful connection of my own useful connection - who didn't mind getting an extra New Year's gift in exchange for a brief phone call to his subordinates who were to issue me a license, without subjecting me to a driving test (which I would have flunked) and ignoring the results of my computer-based driving rules and situations exam (which I did flunk).

In the next four years, I haven't had a chance to drive a car in Ukraine or Russia, and I still do not intend to. The doctors and cops who were so lenient to me and so trustful need not worry about one more potential murderess they've let loose. But even if I do decide that I'm ready to drive, they should not despair, because every now and then I wonder: am I a woman or what? In this part of the world, so many things force me to have doubts about my true gender. And if I'm not really a woman, then what's so dangerous about me sitting in the driver's seat?

I feel uncertain about my womanhood when I drink beer instead of wine or champagne, and when I drink beer more often than once a week, as the narcologist had prescribed me. I feel as an impostor when I announce to a hairdresser that I haven't had a haircut in more than a year, or when I confess to a manicurist that at age 26 (two years ago), this is my first time to have my nails done. Newspapers sometimes give me a mixed feeling of panic and euphoria when I stumble upon paragraphs like this:

"Women are usually not attracted to modest guys in glasses and ragged jeans - they don't consider them men." (My boyfriend of nearly seven years wears glasses, is one inch shorter than I am and has spent a considerable portion of his life wearing jeans and hitchhiking around the Soviet Union. So, am I a woman or what?) "But women immediately fall for the other type of men - those who wear golden crosses and smell of expensive perfume." (My boyfriend's Jewish - that sure does disqualify me from the women's ranks, I guess.) "As a result, it turns out that the first type of men can actually make decent husbands and fathers." (Really? Well, thank you.) "But girls, unfortunately, do not understand this. They keep waiting and hoping, when it is clear from the start that there's nothing here to hope for." (Oh well. I am not one of them, definitely.)

The same newspaper story (see illustration below) recommends women to analyze reasons for their celibacy. Here is how: "In America, there is a university called 'How To Get Married?' Disciplines offered there range from psychology to psychoanalysis, and tuition costs around $75,000. Recently, the rector of this university has created a family with one of the professors. Through her own experience, she has demonstrated that this is a skill that could be easily learned."

"Beautiful, Cold, Lonely..." A family newspaper, Russian style: one possible way of reading this article is to have the whole family - mother, father and their unmarried daughter - sitting on a couch; the mother reads the text out loud, the daughter listens and takes notes, the father admires the picture.

Looks more like a imaginary example of sexual harassment to me, but, as I mentioned earlier, we here have a different perspective on everything. In any case, not married and confused though I am, I would still prefer to do a dissertation on our newspapers. After all, I've already spent a semester in a class supposed to empower women, but ended up feeling nothing but guilt.

Mikhail Zhvanetskiy, the funniest and the most insightful comedian of the Soviet times, once noted that "in this country, the political impact of women during daytime is very low." Once in Ukraine, I was buying newspapers from a man approximately my age while his friend stood nearby and kept saying: "And for yourself? Aren't you gonna buy something for yourself?" It took me some time to understand what he meant: he thought I was buying "serious" papers for a husband (or a father, or a grandfather, or a boss) and wanted me to buy a "girlie" type of publication for my own reading pleasure. I smiled politely and explained that the papers were for me. As I was walking away from their stall, they yelled after me in a friendly unison: "Miss, are you a Congressman or what?!"

And boy, did it make me happy!

No comments:

Post a Comment